The Beginner's Page

Richard Mansfield

Assistant Editor

From Chaos To Bits

Computers are sometimes called data processors. Data is processed by programs. You might type in a list of all the articles in this year's COMPUTE! and then write a program which will show you only the articles on, say, computer music. We will write such a program next month. What we want to see now is how data can be set up in files to make it easier for the computer to process it.

Our list of articles, while interesting in itself, is raw data. It sits in the program as DATA statements (or it could be on a disk or tape file) — the important thing to realize is that a program will later operate on the list, refining it into more meaningful information. The computing (or processing) aspect of this program might be to generate a more specific list: perhaps all articles by a particular author. However, for the computer to process data, the data must be somewhat organized already.

Organizing Data

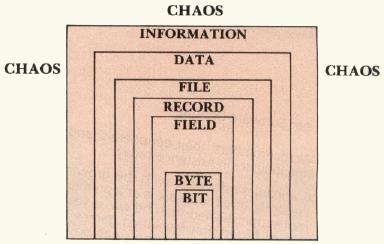

If you look at Figure 1, you will notice that there are a number of divisions, each nested within a larger division. Here is a DATA statement taken from our proposed COMPUTE! index program which will help to illustrate Figure 1.

500 DATA FILES-DATA STORAGE TYPES* MANSFIELD* 17

We can start from the outer ring of chaos and work inward. You make a stack of this year's COMPUTE! If your stack of magazines were burned to ash, the molecules of ink and paper would no longer have any meaningful relationship to each other and could not be called "information." Taken as a whole (as a stack) it is not data, exactly, because data is special: it is information organized so that it communicates a particular meaning. Your computer cannot read (yet), so the articles in COMPUTE! do not become meaningful data for the computer until you type them in as DATA statements or put them on tape or disk files.

Data is divided into files. An entire list of all year's articles is one file. A list of your stocks and bonds would be another file.

Within files there are records. Our DATA statement (line 500 above) is a record. It is a subdivision within the "COMPUTE! Articles File" which refers to a single, logical grouping of information (in this case, the information on a single article). In the financial portfolio file, all the information about a particular stock would be a record. Records are further divided into "fields" of information. We have chosen to use three fields: 1. A description of the article, 2. Author, 3. Issue Number.

As an aside, we should note that there is something special about the first word in our example record. To make it easier on the computer, one part of a record (often the first field, or part of it) is designated the key. Sometimes the key is a number, but we are using the first five characters of the first field ("FILES") as our key. We have decided to key this file by topics. We chose each topic name so that it would be only five letters long. FILES, MUSIC, ART, (notice the two spaces after "ART " to make it five long), ML, (machine language), BASIC, MAPS, INTER (interfacing), DISKS, TAPE, PRINT (printers), MODEM, and any other keys we want.

Bytes and Bits

Finally, the smallest units of information are individual symbols, letters, and numbers. Each single-character piece of information is called a byte. A byte is able to store the numbers zero through 255. Since there are 26 letters in the alphabet, 26 capital letters, and number symbols 0 to 9, and assorted other symbols such as commas and brackets — the number of symbols we use to communicate with is less than 255. So, since a byte can store up to the number 255, each byte can "hold" a number value which represents a particular letter of the alphabet, numeral, or punctuation mark. Your computer stores the number 65, not the letter "A." A code was devised (the ASCII code) which assigns the number 65 to capital "A" and 193 to small "a." Every letter is represented by a particular number. Lower case "b" is 194.

Each byte is made up of eight bits. Where a byte can mean the numbers from 0 to 255, a bit can only have two meanings: zero or one. Sometimes it is useful to think of a bit as being either yes or no, on or off, positive or negative. This "two-state" (binary) bit is often mentioned as the smallest possible unit of information. Even though they have only two states, bits can add up quickly: eight bits together make up a 256-state byte. A grouping of only two bytes can have more than 65,000 possible states—in other words, you could count up to 65,535 using only two bytes.

Processing Data

We have moved down through data from chaos to bits, from the largest to the smallest units. There are many ways to organize fields within records, records within files, and files within a large collection of data (a database). Some thought must go into the structure of this organization so that a program can later process the data efficiently. We decided to use the first five bytes (characters) of each of our records as the key to our COMPUTE! file. Next month we will build a program which will demonstrate some of the techniques of database management. This program will also illustrate the importance of those string-manipulating BASIC commands: LEFT$, RIGHTS, and MID$.