The MS-DOS Invasion

IBM Compatibles Are Conning Home

Tom R. Halfhill, Staff Editor

Thanks to a flood of inexpensive clones from U.S. and Far Eastern manufacturers, sales of IBM-compatible computers have been rising dramatically over the past year. The original IBM PC—which established the standard and once dominated the business market—is now being swamped by workalikes that offer more features for less money. But perhaps the biggest surprise of all is where a large proportion of the clones are ending up.A funny thing happened on the way to the office—the world's most popular business computer found a new home.

Since mid-1985, a wave of so-called PC clones flowing from factories both here and abroad has been forcing down prices of IBM-compatible computers. While an IBM PC with 256K RAM and two disk drives retails for $1,595, equivalent compatibles are available for as low as $600. Machines from Tandy, Leading Edge, Epson, and even Hyundai are popping up practically everywhere. It's been a bonanza for buyers who want machines which can run business software written for the industry-standard MS-DOS operating system. Practically any business can afford to computerize at the prices of today's clones.

But prices have plunged so far downward that a new class of customer is emerging: the home user. Tens of thousands of people are buying IBM compatibles and installing them in family rooms and studies all over the U.S.

The ramifications of this trend are beginning to affect the entire personal computer industry. New clones are sprouting up at even lower prices; hardware companies are busily selling memory expansion boards, video/graphics adapters, hard disk drives, monitors, and other accessories; software publishers are scrambling to meet the increased demand for home-oriented MS-DOS programs; and established companies like Commodore, Apple, and Atari are being threatened on their home ground.

With the biggest buying season of the year upon us, industry analysts are predicting that 1986 will be the year of the "MS-DOS Christmas."

Nipping At The Heels

One of the first companies to seriously challenge IBM for the PC market was Compaq Computer Corporation, founded in Houston in 1982. Compaq introduced its first product—a transportable computer that could run all of the popular IBM PC software—in 1983. It followed with a series of compatibles that quickly found their way into thousands of offices. The fledgling company's skyrocketing annual revenues tell the story. $111.2 million in 1983; then $329 million; $503.9 million; and $291.1 million during the first six months of 1986. In April, Compaq shipped its 500,000th computer.

That kind of growth doesn't escape attention—or eager imitation. Before long, dozens of other companies were trying to cash in on compatibles. Most of them have taken a different approach from that of Compaq, however. While Compaq's prices are comparable to IBM's—and Compaq pushes high quality or special features as a selling point—most compatible makers try to undercut IBM prices as much as possible.

This isn't hard to do, for several reasons. First, the IBM PC's retail price is set relatively high compared to its manufacturing cost in order to provide healthy profits for both IBM and the dealers. The clone makers survive on much tighter profit margins, hoping to make up the difference in volume. They also rely more heavily on mail order sales, frequently bypassing dealers. Too, the IBM PC is relatively expensive to manufacture due to such features as its metal case and heavy-duty keyboard. Compatibles are generally enclosed in plastic cases, have cheaper keyboards, and economize in other ways as well. And finally, most of the compatibles are either imported from such countries as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, or are assembled in the U.S. with components from the Far East.

As a result, it's quite easy to acquire a compatible for hundreds of dollars less than a comparably equipped IBM PC. It's even possible to make your own compatible by buying the components and plugging them together. (See the accompanying article, "Cloning Your Own Compatible.")

But lower prices aren't the whole story behind the success of the compatibles. Many of them offer advantages in terms of features and performance, too.

Again, this isn't as difficult as it may seem, even though the clone makers are dwarfed by IBM's vast financial and scientific resources. The IBM PC has remained essentially unchanged since its debut in 1981, and it was conservatively designed even back then. Many of the compatibles offer faster microprocessors and clock speeds— sometimes 100 percent faster; more standard memory; built-in equivalents of IBM's video-adapter boards; half-height floppy disk drives or hard disks; bundled software; and sometimes more room for future expansion, since the built-in memory chips and video adapters don't occupy card slots.

Migrating Home

When you add up all these advantages, you'd expect businesses to be snapping up compatibles as bargain-basement alternatives to the IBM PC—and they are. But business sales alone can't account for the clone boom.

For one thing, some businesses are wary of compatibles. They'd rather pay the premium for an authentic PC because of IBM's reputation for quality, service, and full compatibility. Although the clones are generally reliable and about 99 percent compatible, there's still a chance that someday the machine could break down or refuse to run a certain piece of software—and that day is dreaded by the employees responsible for the purchasing decision. The old corporate adage "Nobody ever got fired for buying an IBM" still rings true.

Consumers, on the other hand, find the clones more attractive. People tend to be thriftier when they're spending their own money, and the difference of a few hundred dollars that might not be significant to a business can loom large in a household budget.

Something else that makes IBM compatibles attractive to home users is the secure feeling of buying into an established standard: MS-DOS. Other computers may offer more advanced technology at a comparable or lower price, but thousands of programs are available for the IBM PC, and the standard seems here to stay. This is enough to sway some of those who've been hesitating because of the volatile nature of the home computer market.

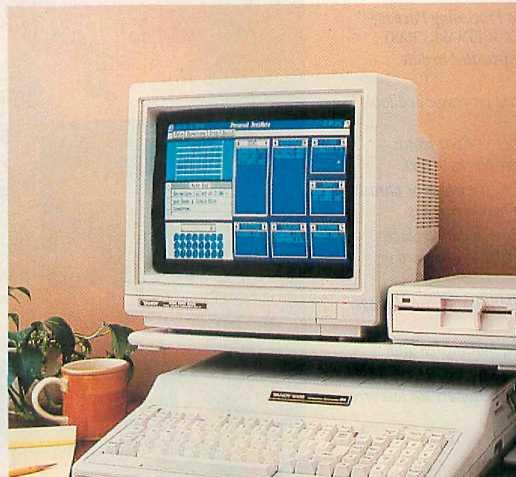

The new Tandy 1000 EX is a typical example of the low-priced IBM compatibles that are crossing over into the home and educational markets.

Clones On The March

No one knows for sure exactly how many compatibles are ending up in the home, since manufactures quickly lose track of their machines after they're sold. But various sources indicate that a sizeable percentage of IBM clones are not ending up in the office.

For instance, one of the most popular IBM compatibles has been the Tandy 1000, which enjoys wide distribution through Tandy's chain of Radio Shack stores. Tandy estimates that roughly half of its IBM compatibles are now going into homes.

In fact, Tandy was so impressed with the success of the 1000 that it recently introduced two new models at even more attractive prices: the 1000 EX and 1000 SX. Both computers are certified by the Federal Communications Commission for use in the home (where broadcast-interference standards are stricter than for computers used in offices). The 1000 EX even has such unusual features as a headphone jack and volume control for private use in home and classroom settings.

Another indication that IBM compatibles are on the march is that the number of computers costing more than $500 is steadily increasing in the home. According to a study conducted by Dataquest, a market-research firm in San Jose, 52 percent of the computers installed in U.S. homes in 1986 cost more than $500; over a third cost more than $1000.

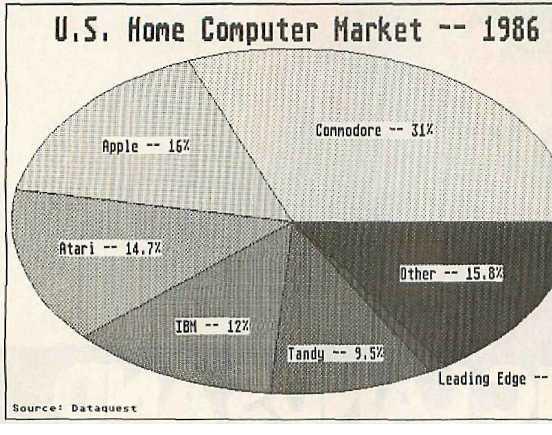

Dataquest also found that IBM PCs and compatibles—formerly a negligible force in the home—are rapidly gaining market share, IBM's share of the home market jumped from 8 to 12 percent between 1985 and 1986. Tandy/Radio Shack computers overall have a 9.5-percent share (although this includes non-IBM compatibles Like the Color Computer and TRS-80 laptops). And one compatible that wasn't even available in 1985—the Leading Edge Model D—suddenly appeared in the 1986 statistics with a 1-percent share. (See chart.)

The Ripple Effect

The most common explanation for the recent success of the clones is that people are buying them so they can take work home from their IBM-equipped offices. The idea is that people are spending their spare time slaving over spreadsheets and reports. Certainly this accounts for much of the increase in sales. But not everyone is that dedicated to their job, as indicated by the simultaneous jump in demand for entertainment-oriented MS-DOS software.

"That's probably why they bought the machine, so they could bring work home," acknowledges Gary Carlston, chairman of Broderbund Software in San Rafael, California, "But there's certainly an increasing demand for all kinds of home software. The game market—we're hearing a lot of requests for more games and a lot more educational software to run under MS-DOS. We traditionally have not made much of an investment in IBM software because it's our perception that people in the first couple of years bought an IBM and Lotus 1-2-3 and not much else. But it appears that they do want software, and that we would benefit from having a lot more,"

As a result, Broderbund has been stepping up its production of MS-DOS software, and other home software publishers are doing the same.

"It's kind of interesting because we decided to do a lot more development for IBM at about this time last year," says Robert Botch, vice president for marketing at Epyx Software in Redwood City, California. "We anticipated some price-dropping and some other people getting into the market. Particularly, it was obvious that Tandy was selling an awful lot of IBM clones. Our sales definitely have been increasing month by month, with more and more of the clones being sold,"

Significantly, Epyx sells no business or productivity software for the IBM at all. "Most of our IBM software is sports games," says Botch. "Summer Games II, Winter Games—those have been real popular in the IBM market. Our baseball game is selling very well on the IBM, too. I think we've been finding that there have been business people buying IBM clones, but the big difference has been with the people taking them into the home. If you're looking for a reason to justify it by saying, 'Oh, I may bring some work home so I can work on the weekends or in the evening,' it makes an awful lot of sense. If you're looking for some reason to spend that $1,000, it helps to explain…why you're bringing this funny-looking piece of hardware home."

That's Entertainment

Another company that noticed its sales of IBM entertainment software picking up in late 1985 is Electronic Arts of San Mateo, California. EA responded by developing its first programs specifically for the IBM, instead of converting titles originally designed for other machines. All of EA's programs are games, though they tend to be more sophisticated than shoot-'em-ups: Starflight, a role-playing game; Grand Slam Bridge, for card players; World Tour Golf; Chessmaster 2000; Venture's Business Simulator; and others.

"We've found that people who buy their computers primarily to do spreadsheets at home are spending 22 percent of their time playing games, and people who buy their computer as a hobby are spending 22 percent of their time playing games," says Bing Gordon, EA's vice president for marketing. "So although I think the lead justification for buying the clones is not game playing—it's the better-understood computer applications like word processing and spreadsheets and kind of a hint of self- improvement—a good game on a computer is a pretty satisfying experience. A lot of people will discover that."

Like Broderbund, Epyx, Electronic Arts, and other companies, Spinnaker Software of Cambridge, Massachusetts, also noticed that sales of its IBM titles started rising dramatically during the past year. Spinnaker, too, has responded by introducing more MS-DOS programs for home users. Spinnaker is somewhat different, though, because it has always designed all of its software on IBM-based development systems.

"But in the past, we sometimes held back the IBM version simply because there wasn't much of a market for it," says William Bowman, president of Spinnaker, "Now we're always marketing IBM versions on everything that comes out. I think that parents in particular are interested in getting a machine for the home for their children to learn on, to use as a word processor for their schoolwork, and things of that sort. I think that's exactly what we're seeing."

The True Home Computer?

All of this sheds new light on an old debate: When is a personal computer a home computer? And what exactly is a home computer, anyway?

Most computer companies have been shunning the home-computer label in recent years, even when the majority of the machines they sell are going into homes. For instance, during a panel discussion at an industry trade show, Apple Chairman John Sculley emphatically denied that his company is selling home computers. Apple, he maintained, sells "computers for use in the home."

The distinction, supposedly, is that a home computer is a low-powered, low-end machine primarily suited for playing games, and that a personal computer is more practical and pricey. But now that IBM compatibles are selling at the same prices of the home computers of a few years ago—and their owners are demanding more non business software—the industry may be forced to rethink its traditional definitions of the home-computer market.

Ironically, the compatible makers seem to be succeeding exactly where IBM failed two years ago with the PCjr: They're selling computers to people who want to take work home from the office now and then, play a game now and then, learn more about computers, and help educate their children. It's obvious that the clone makers learned from IBM's mistakes. Unlike the PCjr, the clones are relatively inexpensive, as fast as or faster than a PC, highly compatible, and are perceived as serious computers.

"The PCjr wasn't standard," says EA's Bing Gordon. "Clones have tried much more wholeheartedly to adopt the standard. IBM tried to create a new standard for the home, and I think they misjudged how easy that would be to do."

Slicing Up The Pie

While many hardware and software companies are racking up big sales because of the clone boom, a few other players stand to lose: Commodore, Apple, and Atari, the computer manufacturers which have traditionally dominated the home market.

All three companies are particularly vulnerable to the compatibles right now because they're trying to establish new computers in roughly the same price range. The Commodore Amiga, Atari ST, and Apple IIGS are aimed at the same $500-to-$1,500 market as the clones. These three machines are also being advertised as powerful and versatile enough for home, business, and educational applications—just like the clones. At the same time, there's that trend away from the under-$500 computers which have been staples for Commodore and Atari.

Although Commodore leads the home market, most observers think Apple will lose more ground to the compatibles because of its market position. "I think that the IBM-clone customer so far has been real different from the Commodore 64 customer," says EA's Gordon, "Maybe the Commodore 64 customer is a teenage boy or a male 25 to 40 whose primary interest in the computer is to buy it for his own use and to learn about it—a little more of a hobbyist use, hobbyist/ business. And the Apple has traditionally been the family computer, with a lot more mothers involved in the purchase of Apples.

"Now, what we've seen among our own customers," notes Gordon, "is that the IBM customer tends to be very similar to the Apple customer—a lot more family-oriented, a lot more influence of mothers over the purchase, with a real similar kind of ranking of what they think are important applications: productivity first, education second, and entertainment something they don't really like to talk about. If you look at the numbers, Apple II sales have gone down as clone sales have gone up."

Broderbund’s Gary Carlston agrees: "This is definitely the MS-DOS Christmas. I think it will be as big as Apple's, which has probably never happened before." But Carlston thinks the ST and Amiga will weather the storm a little better: "I don't see them as being the same users. ST and Amiga users are people who know what they want. People who buy MS-DOS clones are kind of bringing [them] home from work, and I don't think in most cases have made a decision to buy that over an ST or an Amiga. I think people need to worry about the Apple IIGS a lot more."

The Sincerest Form Of Flattery Forever

Meanwhile, others worry about the sleeping giant—IBM. How long will IBM watch its PC sales eroded by the clones without taking retaliatory action? To make matters worse, IBM's latest personal computer, the AT, also is being smothered by clones that offer more features for less money.

Some observers are awaiting a "clone-basher," a lower-priced PC that will match the clones. Others point out that IBM has never competed at the low end and instead will introduce a proprietary operating system or a new line of graphics-oriented computers in 1987.

The IBM-compatible market is so lucrative, however, that anything IBM does in the future will likely be cloned no matter what the obstacles. IBM may have to resign itself to tolerating the sincerest form of flattery forever.