Is There Too Much?

BY AMY H. JOHNSON AND RICHARD P. GREENFIELD

It's a fact that most computer games contain some violence. But when is there too much? Is there a fine line between "acceptable" violence and excessive violence? Are there industry standards that guide the presence of violence in games? And how does this violence affect children? In a provocative study, START sought answers to these questions based on games currently available for the ST.

Playing computer games, you can save Earth from aliens, fight crime, explore dungeons, spend a night in a haunted house, deliver papers, learn math or navigate a maze. You can be a sports star, soldier hitchhiker, amnesiac, archeologist or frog. But you can also shoot, stab, kick, cut or bomb people; blow planes out of the sky, toss grenades into an Asian village or launch nuclear missiles at obstacles in your path.

Computer games are a $260 million a year business, according to the Software Publishers Association. By some estimates, 80 percent of that money is spent on violent programs that may adversely affect those who play them. Most affected are children and teenagers, who game makers say are a large percentage of players. More than 150 groups across the country endorse a boycott of war toys, some going so far as to propose that the computer game industry be regulated like any other that produces a dangerous product. Spokespersons for software publishers say their games are no worse than many other forms of entertainment and that they're only producing what consumers want. Here's a look at the controversy and a few of its causes.

Operation Clean Streets

Your orders come directly from the Chief of Detectives: wipe out the

nicotine ring. It's a dangerous assignment. The instruction manual for

Broderbund's Operation Cleanstreets warns, Tracking down your foes is just

the start. Because they'll never surrender without a struggle. You'll have

to outfight them every step of the way. Kicking. Punching. Dodging." And

that isn't hyperbole. You don't make arrests in this game, and the "dope"

you confiscate isn't held for evidence. It has to be burned in a convenient

ashcan fire and when it goes up in smoke, you get extra energy to go about

finding and seizing and destroying even more.

In Broderbund's Operation Clean Streets

your

orders come directly from the Chief

of Detectives:

wipe out the nicotine ring. You don't

make arrests

in this game, and the dope you confiscate

isn't

held for evidence.

You operate in a series of ghetto cityscapes - littered streets lined by brick tenements, docks, dingy basements, deserted basketball courts. One attacker tries to knife you, another tries to whip you with a chain and yet another tries to slice you with a chainsaw. When you run back to throw the dope in the fire, angry neighbors fling bricks at you from the windows. You encounter and battle bat-wielding black people wearing neon pastel clothes and hightops, ninja-suited Asians armed with samurai swords and shuriken and a leather-clad woman with a bullwhip.

"When we first got the game it was a little different," explains Jenay Cottrell, a spokesperson for Broderbund. "We added the black Chief of Detectives, and we emphasized that this person was out there fighting crime. There really is no effort to key on bad stereotypes. We did make an effort to show a broad range of criminals that this undercover cop is going up against."

Broderbund has no written policy to review the contents of games, but Cottrell says each project is reviewed by a committee consisting of eight to nine people, including the president, the chairman of the board and the chief operating officer of the company.

According to Cottrell there have been no complaints about the content of Operation Cleanstreets. "Actually, we have gotten some letters telling us how much some users enjoyed being in the shoes of someone fighting crime," she says.

The players of Operation Cleanstreets, according to information provided by Broderbund, are predominantly male between the ages of eight and 18. Broderbund considered the possibly desensitizing effects of graphic video game violence, "but when you compare it to some of the other games out there," Cottrell says, "or even to what is shown on television, this cop is out there fighting crime . . . at worst this is what we call a karate-type program, just one of a number of games where you are a good person fighting evil."

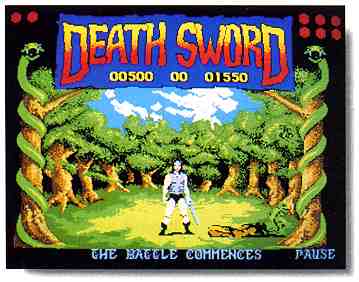

Death Sword and Technocop

You are Gorth, son of kings, heroic, honorable and skilled with a sword.

Off you go to right an injustice, the kidnapping of the beauteous Princess

Manana by the unscrupulous sorcerer Drax.

Death Sword, from Epyx, gives you two

ways

to kill Fundor (and for him to kill

you). One way

is to hack him to death, bit by bit.

Or you can

chop off his head.

In Technocop, also from Epyx, your

mission is

clear: "Eliminate all thugs before

they eliminate

you."

Some of the people you meet in Sierra

On-Line's

Manhunter: New York aren't exactly

friendly; for

example, if you fail to win over the

denizens of a

seedy Brooklyn bar one will pick you

up and

crush your head. Save your game often

because

the tiniest slip and you're history.

But the programmers of Epyx's Death Sword put a few obstacles in your way, notably Drax's guard Fundor, as skilled with a sword as yourself but lacking your purer qualities. You must battle Fundor in an enchanted forest, a lava pit, the dungeon of Drax's palace and in his throne room. And no matter how often you kill Fundor, another swordsman appears for your next encounter.

There are two ways to kill Fundor (and for him to kill you). One way is to hack him to death, bit by bit. To do this you must deliver 12 body blows, which are indicated by red blood splotches appearing onscreen. Or you can chop off Fundor's head and see it tumble from his shoulders while a red fountain of blood shoots skyward from his neck. His body topples to the ground and a knee-high green hominoid drags it away, kicking the severed head off-screen.

In Technocop, also from Epyx, you start off behind the wheel of a high-tech cop car that barrels down the road, heading for the crime scene displayed on your dashboard computer. Depending on your skill level your car may be armed with a machine gun, a rapid fire cannon or even small tactical nukes. Lest that seem like overkill, the instruction booklet is quite clear: "Remember the golden rule of crimefighting: Eliminate all thugs before they eliminate you."

Welcome to the world of high-tech law enforcement. Around your wrist is an all-purpose crime computer that displays the suspect's identity, orders to eliminate the criminal or bring him back alive," radar that indicates the direction of your prey and two weapons. One is a lethal .88 magnum and the other a net gun that just immobilizes the target and takes longer to deploy.

At the first crime scene you are attacked just outside the entrance to a run-down building. But be careful! A little boy plays between you and your attacker If you fire your magnum, your attacker explodes into a pool of twitching. bloody sludge. But the child accidently gets in the way and also falls down into a lifeless heap. Killing an innocent bystander costs you 5,000 points, but it may get you into the building faster. It's just a trade-off in Technocop.

"Many forms of entertainment contain a certain amount of violence," Epyx spokesperson Don Transeth points out. He includes toys, TV, movies, arcade games. comic books, cartoons and sports as examples. "So it's kind of hard to put a stake in the ground in the computer game area and say that this is the one making people do things they wouldn't ordinarily do," he says.

Epyx has not had any formal meetings to discuss the possible harmful effects of violent games, but "we do review all our products, carefully, as you can imagine," Transeth says. The company however, has no written policy or standards regarding game contents, according to Transeth. Epyx develops a wide range of games, he explains, some of which, in the action genre, are more violent than others. Such games are a small percentage of their overall product line, Transeth says, but he is unsure of the exact number.

Manhunter: New York

Thirteen years in the future, aliens invade Earth. Two years later,

some humans are still fighting, but you're a collaborator, a Manhunter.

Your job is to track down and eliminate resistance to the Occupation. Your

instructions are to "conduct yourself in a manner suitable to your position.

Treat your fellow earthlings with the indifference they deserve."

Sierra On-Line's Manhunter: New York begins with you tracking the illegal human resistance to Bellevue Hospital. On your arrival, you see the resistance has blown a hole in the hospital wall, directly opposite the morgue. You walk in and are confronted with a toe-tagged, green corpse and learn one of the aliens' secrets: they gestate in the exposed chest cavity of dead humans. If you don't move away quickly enough, a swarm of them flies off the corpse and eats away your face right down to the skull.

This is a puzzle game, requiring you to negotiate mazes, demonstrate physical skills and unravel clues. Some of the people you meet aren't exactly friendly; for example, if you fail to win over the denizens of a seedy Brooklyn bar one will pick you up and squeeze your head until your skull explodes and your brains splatter on the ceiling. Save often, because failing any of the tests can get you killed.

"It is our general guideline to tend away from violence in our games," Sierra On-Line spokesperson Kirk Green says. "Manhunter is the exception to that rule," Green claims.

The company has no written policy about what kinds of violence can be represented onscreen, according to Green. He says not many children will be exposed to the explicit depictions of death in Manhunter: New York because "younger kids cannot afford the game as much. These games usually go to more of an upscale audience, mostly adults and more of a sophisticated science-fiction fan crowd."

Lucasfilm Games

At the games division of Lucasfilm Ltd, General Manager Stephen B.

Arnold says, "We have no published standard, but a personal standard not

to do anything particularly violent like a 'hack-and-slash.' We might do

a representational violence - a fantasy, a human fighting an alien, for

instance - but not human beings hacking and slashing other human beings

in a graphic and gratuitous way, especially in a game targeted to kids."

By way of example, Arnold cites the new ST Lucasfilm game Battlehawks 1942, which portrays aerial combat in the Pacific theater in World War II. A player may choose to play either the American or the Japanese side, however, when an opposing plane is shot down, the pilot bails out and the game does not permit the victorious pilot to strafe the pilot parachuting to safety. Arnold says this lockout was deliberate and representative of standards that ". . .we evolved ourselves and set our own creative standards. We are part of a company that considers itself a family-entertainment business. Just as Lucasfilm wouldn't do a slasher movie with all the cinematic gratuitous violence, we wouldn't do a slasher game for the same reasons."

Asked about the proliferation of violent games and their popularity, Arnold replies "I haven't seen all of them but there is no doubt there are some things out there that are inappropriate. 1 think that the same rules need to apply here as in other entertainment projects - it is possible to represent those things, violence and conflict, which are a part of our world in a context which is not gratuitous or shocking." Arnold also notes, parenthetically, that the games division at Lucasfilm is profitable without the explicit blood and gore.

National Coalition Studies

After playing Manhunter: New York children aren't likely to crush their

playmate's heads; neither are they likely to hack their playmates after

playing Death Sword, or find a gun and kill someone after playing Technocop.

But copy-cat violence does occur in about one percent of the cases known

to psychiatrist Dr. Thomas Radecki, founder of the National Coalition on

Television Violence. The effect that his research has found is mostly a

short-term increase in aggression.

In a study where he observed the playground behavior of preschool, second and fourth graders after playing with a Captain Power gun, building with construction toys and doing schoolwork, Radecki measured an 80 percent increase in hostile chasing, hitting, hair-pulling and sitting on top of other children after the interactive gun game. And while he concedes that daily fluctuations in children's aggression are extreme enough to account for the increase, he says he is virtually certain, based on his research and eight other studies, that violent computer games produce harmful long-term effects.

"The very minimum we should do is treat them like any other dangerous

consumer product," he says, and put

warning labels on the package. He lists their possible bad effects,

such as desensitization to violence, thinking violence solves problems,

increased acceptance of militarization policies and a tendency to slip

into violent behavior when faced with a real-life conflict.

Radecki says newer computer games are "more intense, more graphic and undoubtedly more harmful." They depict more realistic people and weapons than those of a few years ago, he explains, and the trend is to make the player participate in "clear, aggressive acts by a character with whom (they) can easily identify." Lessons learned in these games, he claims, are much more likely to be carried over into the real world.

Radecki approves of Texas Instruments' line of educational video games, Donkey Kong, Jr. Math, Sesame Street games, exercise video games, some sports games and skill games like Paper Boy. He also says games like Pac-Man aren't harmful because their violence is abstract and not easily imitated. In real life, a person can't swallow a ghost.

Larger Questions

Questions about the content and explicit violence in computer games

raise larger questions about these same characteristics in other forms

of popular entertainment. Game makers point to television as a more pervasive

source of explicit violence; so, for that matter, are the "other guy's

games." All of which begs the real question of what standards, if any,

should game makers follow, and how can they be inspired in the face of

countervailing market pressures?

Amy H. Johnson played her first computer game, Adventure, 11 years ago. She works as a software developer and freelance journalist. Richard P Greenfield is an internationally published columnist on Pacific Rim technology with emphasis on the entertainment industry.