THE HOTZ MIDI TRANSLATOR

Atari Team Redefines Electronic Instruments

BY CRAIG ANDERTON

Most MIDI devices are a kluge between old instruments and new technology. Jimmy Hotz, working with Atari, invented a new way of creating electronic music, one which bridges the gap between a computer's abilities and a composer's creativity. Here's an overview of what Atari is offering musicians in stores today.

|

| A complete set-up, including a Stacy, a Hotz Box and wing unit. |

Although musical electronics and its relationship to computers has changed drastically over the past few decades, one element has hardly changed at all--the ways that players interact with the electronics. The most common synthesizer interface, the keyboard, was designed centuries ago to trigger mechanical systems, not electronic ones. Although a few concessions, such as polyphonic aftertouch and mod wheels, have been made to the age of electronics, the keyboards we play today are very similar to those that Bach played.

Even "alternate controllers" are more likely to mate other devices designed centuries ago (guitars, wind instruments, drums) to modern electronics instead of providing a true alternative to conventional interfaces. Surely there must be novel ways to relate musical gestures to computers and synthesizers?

Apparently record producer/engineer Jimmy Hotz thought so, too, and teamed up with Atari to manufacture a new controller, designed from the ground up, to interface with MIDI music devices and computers, although it is not necessarily limited to those applications. The birth of the Hotz MIDI Translator (nicknamed the "Hotz Box") has not been without controversy. Reactions vary from "it just lets non-musicians play along with CDs" to "this has the potential to change the music industry."

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Translator is its ability to fit so many different roles. Beginners without any knowledge of MIDI or musical electronics can use it as a "plug and play" device, but it is also a serious tool for professional composers, players and educators who do know a lot about music. Welcome to the 1990s, and one of the most fascinating, unusual, intimidating, musical and enigmatic devices I've run across in quite some time.

Getting to Know You

There are two basic parts to the Hotz Translator: the hardware controller itself, which replaces a traditional electro-mechanical keyboard, and the software, which translates your finger pokes into MIDI data. Unlike familiar keyboards, guitars or wind instruments, the playing surface of the Hotz Translator is a flat bed with no mechanical moving parts. In their place is a bevy of touch-sensitive rectangular pads. Simply touching one or more pads generates control signals which are immediately detected and routed to the Atari computer. The software converts the control signals into MIDI-note or expression data, depending on the function currently assigned to each pad, then back out of the computer and on to the destination MIDI instruments or equipment.

The hardware controller unit is substantial: large (37 inches by 22 inches), heavy and expensive (somewhat less than $6,000). Part of the reason for the cost is that the internal electronics need to be quite sophisticated to handle the huge amount of data the Translator is capable of creating. Ten parallel processors collect and merge all the data for output, resulting in extremely fast operation. Even under worst case conditions, it takes less than seven milliseconds between the time you touch a pad until its resultant MIDI data is output by the Atari computer. This is lightning fast compared to standard keyboards, which can take from seven to 180 milliseconds due to mechanical action time, keyboard scanning lags (determining which keys have been pressed) and time to sense low-velocity notes. Why such high-performance hardware? Hotz envisions the Translator as a universal "controller platform" for many applications, current and future, MIDI and otherwise. The more horsepower that's available, the fewer limits it may encounter later.

|

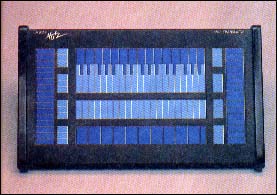

| Figure 1: The Translator's pads, based on force-sensing resistor technology, are arranged in five groups. |

Touch and Go

The surface of the main controller unit holds five groups of pads. These are touch sensitive, based on force-sensing resistor technology, and designed for triggering single or multiple notes. The pads (see Figure 1) are arranged in two vertical strips of 16 along the left and right sides, one horizontal strip of 11 large pads toward the bottom, 21 narrower pads directly above those, and a group of pads laid out more or less like a three-octave keyboard towards the top of the unit.

There are also four groups of three pads dedicated to producing signals such as modulation or pitch bend. These spotlight the underlying force-sensing resistor technology, since they enable expressive nuances that have to be played to be believed. Tricks like bending up by a certain interval and then wiggling your finger to produce vibrato are easy to do and controllable. Hotz was trained as a guitarist, and his desire to translate some of that instrument's abilities to his controller is clear.

In addition to the pads, the controller unit has six, one-quarter inch auxiliary input jacks and eight RS-232 serial ports. The auxiliary inputs can be used for additional note and/or control effects such as volume, note transposition and sustain. For example, you can trill your fingers between two note pads while using a foot pedal to sweep up and down octave ranges. The controller unit itself connects through its MIDI Out port to the MIDI In port of an Atari computer.

Additional wing units can be hooked into the main unit, giving you additional pads to expand your controller system. These wings are similar to the main unit but smaller and with different pad layouts.

Translation Service

The translator software takes incoming signals from the controller unit and converts them into conventional MIDI data. When you consider that each pad has its own set of definitions for what notes or controller data are to be sent, that these definitions can be reassigned on the fly, and that there are numerous pads feeding data into the computer simultaneously--well, we're talking very impressive, sophisticated software. The initial version of the Hotz Translator software filled the computer screen with an intimidating series of numbers and symbols, making the cockpit of a 747 look like child's play by comparison. Thankfully, this has been simplified and continues to be refined as the system matures. It's also worth remembering that you don't have to use all the features all the time. In fact, it's best to think in terms of simple chord progressions and song patterns as you get used to the Hotz Box.

There are three main parts to the software setup. These structures can be considered independent data processors: the upper bank, lower bank, and zoom bank. Each bank contains "cells" with assignments relating notes to specific pads. Generally, the upper bank contains a collection of chords that will be used in a given composition, the lower bank contains scales and the zoom bank provides instructions for changing the assignments on the fly.

The Hotz software contains one of the most complete libraries of chord structures in the world. Any chords, from simple majors and minors to extremely complex and exotic voicings, are easily set up and assigned to desired pads. Yes, touching a single pad can actually give you all the notes for an E minor 7th with an added 9th over multiple octaves, if you so desire. Literally, over a billion chord voicings are possible with just a single row of pads.

Is your hand too small to span wide chords? The translator eliminates such physical limitations, a special blessing for handicapped players frustrated by conventional instruments.

The lower bank usually contains the scales that will be played on the pads you've designated for melodies, as opposed to chord clusters. Special pitch bend effects are built into the Translator's repertoire to produce tones "between the cracks" of normal keyboard semitones and to emulate ethnic scales. Assigning a pad to select a cell from the zoom bank automatically changes the assignments in the upper and lower banks according to specifications you've programmed into the zoom cell. This is the key to the Translator's operation: its character can change dynamically as you play. It lets you concentrate on bringing the musical ideas from your brain into reality rather than focusing on the physics of placing the correct fingers in the correct places.

All of this is a rather simplistic overview in that the Translator can send data over multiple MIDI channels, set up system exclusive strings, add vibrato, transpose, and much, much more. The Translator allows for a fluid, transparent alteration of the relationship between input and output, much in the way that a movie camera combines still shots so rapidly they appear to be moving.

Trying to learn all the complexities of the Translator is a daunting task. Fortunately, there are enough defaults so you can get "on the air" with minimum fuss; once you have the basics firmly in hand, you can plumb the depths of the controller at your leisure. The possibilities seem limitless, but magazine space is not, so let's zero in on one common way to use the Translator.

The Brain/Instrument Connection

To understand the Translator's main appeal to professional musicians requires a bit of understanding of how a musician makes music. Most musicians agree that getting music from their heads out through an instrument is an imperfect process at best. Glitches often occur as nerve impulses travel down your fingers to a musical instrument. You might hear a great 64th-note run in your head, but not be able to play that fast due to limited dexterity. Or you may hit a wrong note, throwing off your concentration.

There are other problems as well. Keyboard players know how difficult an interval of a tenth is to play one-handed, but those with small or inflexible hands may not be able to play a tenth at all. Guitar voicings also are subject to limitations; among other things, you can't play two notes on the same string at the same time. A guitar can give wide-open musical voicings, but clustering many close by notes into a chord is difficult.

Another point is that most musical instruments are inherently inefficient devices. For any musical idea you want to play, many of the keys on a keyboard or frets on a guitar are unnecessary and unused. For example, if you're playing a C major scale on a keyboard, the black keys are useless unless you need to play them to shift into a different scale, in which case some of the white keys may now become useless. Being able to hit notes that are not part of the scale in which you work can lead to "wrong" notes.

The Translator attacks these problems in a unique way. Its software reconfigures notes triggered by the pads, on the fly, so there are no useless notes. For novice musicians, this means you can't make any mistakes because it is impossible to hit a bad note. As you might expect, accomplished musicians tend to scoff at musical instruments that don't allow for mistakes. Most such novice-oriented devices are so restrictive that an advanced musician will rapidly lose interest.

The Hotz Box avoids this trap. If you know music, you can configure scales so that, for example, the third or the fifth will always show up on the same pad in a group of pads, regardless of the musical key. If you hear a seventh in your head and want to play it, you'll probably be able to pick it out instantly, thus streamlining the brain-to-instrument connection. Should you hit the wrong note, at least it will fit with what you're playing.

Jamming with Mick

So what's this about playing along with CDs? The Translator can reconfigure itself not just in response to using pads, but also through MIDI program change commands (and if driven by a SMPTE-to-MIDI converter, via SMPTE time code). Hotz expects to exploit the new CD+MIDI specification and is encouraging the artists with whom he works to embed within CDs the "cues" necessary to drive the Translator.

The first of these "cued" CDs will be from Mick Fleetwood, slated for a late 1990 release; other artists are in various stages of incorporating this process into their own releases. Consumers with a CD + MIDI-equipped CD player can simply plug its MIDI output into the Translator and play along with their favorite artists--no programming, set up or other brainbending tasks required. Playing music doesn't get much simpler than that.

Granted, at its present multi-thousand dollar price tag (not counting the computer) few non-professionals will buy the Translator. Atari's plans, however, call for eventual downscale models of the Hotz controller, culminating in a low-cost, mass-market item to be distributed through K-Mart-type outlets. To appeal to consumers, there also will have to be significant growth in the CD player market. As of today, only JVC manufactures a MIDI-equipped CD player and it is a bit pricey.

Reality Check

There are some limitations to this musical blue sky. The current translator software does not let the pads produce aftertouch, a common MIDI-modulation control. The hardware is capable of doing it but, considering the number of pads, the resultant signal load could easily overwhelm the MIDI communication channels.

Since the software is an integral part of the system, you can't use the Translator without your Atari computer (although the Stacy laptop would be fairly compact). Perhaps a more serious consideration is the long learning curve if you want to master the instrument. On the other hand, learning keyboard or guitar isn't all that easy either; there's no getting around the fact that mastering an instrument, not just bashing on it, requires dedication and practice.

Fortunately, the Translator can do some very satisfying things right out of the box. When I first received one for evaluation, I was immediately sucked into playing some wonderfully huge chord voicings and matching melodies using preprogrammed software. For songwriters, the Hotz Box is a dream come true, offering instant access to all the components of music but requiring little, if any, playing chops. The easy accessibility also promotes serendipitous events, where you hit something you didn't intend to and produce something better than expected. The preliminary manual advises having a sequencer going at all times to capture any good ideas that come along; I can certainly vouch for that.

The Hotz Translator is not vaporware--it is real, currently shipping and in use today. It is manufactured in the United States and sold directly through Atari. Various price estimates have appeared in different articles--these reflect a variety of bundled configurations of main unit, side wings and computer. Fleetwood Mac used it on their recent "Behind The Mask," album and are using it on their current, Atari-supported world tour.

It is also being used for much more humane and rewarding purposes--as a means for handicapped and autistic children to make music and express themselves. In one such instance, Atari recently donated a Hotz Box, computers and peripherals to the Children's Hospital of Stanford University.

In its present state of development, the Translator is too expensive for many musicians, and potentially quite overwhelming at first. However, Hotz continues to streamline the user interface and Atari has its eye on lowering the cost. The first fruit of this is the Translator II, a new lower-cost version ($3000) that was introduced at the past summer's National Association of Music Merchants show. This is a smaller, more portable unit, dedicated to musical applications. With innovations like this, the marriage of Atari and MIDI seems destined to be a long and happy one.

Craig Anderton is the founding editor of Electronic Musician magazine and a recognized expert on MIDI, with several books to his credit. this is his first article for START.

PRODUCT MENTIONED

The Hotz MIDI Translator, call for price. Atari Corp, Music Division, P.O. Box 61657, Sunnyvale, CA 94088, (408) 745-4966